Volume : 1 | Issue : 1

Clinical Paper

Incidence of stillbirths and risk factors at a tertiary perinatal center in Southern India: retrospective observational study

Kallur Sailaja Devi,1 Nuzhat Aziz,1 AnishaRamniklal Gala,1 Tarakeswari Surapaneni,1 Divya Nair H,2 Hira B Pant2

1Department of Obstetrics, Fernandez Hospital, India

2Indian Institute of Public Health, India

Received: June 29, 2018 | Published: July 26, 2018

Abstract

Objective: The objective was to evaluate the aetiology and risk factors for stillbirths.

Design: A retrospective observational study.

Setting: Tertiary perinatal institute in Southern India.

Sample: 436 stillbirths out of 40,374 singleton births from 24weeks of gestation, delivered during 2010 to 2015.

Methods: The risk factors for stillbirths were derived from maternal characteristics, past medical history, pregnancy complications, intrapartum details and fetal characteristics and analyzed using univariate and multivariate methods. ReCoDe classification was used to find the etiology of stillbirth.

Main outcome measures: Incidence of stillbirths and its association with the risk factors.

Results: Incidence of stillbirth was 10.79% /1000 for births more than 24weeks of pregnancy. Multivariate analysis showed referred women (RR 24.16, 95% CI 19.99–29.20), fetal growth restriction (RR 5.17, 95% CI 4.23–6.30), antepartum haemorrhage (RR 6.09, 95% CI 4.48–8.26), and acute fatty liver of pregnancy (RR 26.62, 95% CI 14.10–50.26), were found to be significant causative factors. Recode classification had fetal growth disorders as the leading cause of deaths in 123(28.2%) followed by hypertension disorders in pregnancy in 67(15.3%) and unexplained stillbirths in 56(12.8%).

Conclusion: The leading cause of stillbirths was fetal growth restriction and hypertensive disorders in pregnancy. Identification of risk factors, improving detection of fetal growth restriction, appropriate and timely intervsention in pre-eclampsia may reduce stillbirths.

Keywords: stillbirths, incidence, risk factors, causes, southern india

Introduction

Stillbirth has a traumatic effect on the life of a woman and her family. It has been a worry that reduction of stillbirths was not regarded as one of the Millennium Development Goals and is still missing in the Sustainable Development Goals. The World Health Organization (WHO) has reported 2.6million stillbirths in the year 2015, globally.1,2 India continues to be at the top of this list recording a massive 592,100 stillbirths in the year 2015.3A vast majority of stillbirths are preventable.4 Many risk factors have been associated with stillbirths. Strategies for reducing stillbirths require an analysis of etiology and risk factors as a first step. A risk factor is defined as any attribute, characteristic or exposure of an individual that increases the likelihood of developing a disease or injury.5 The major causes for stillbirths have been child birth complications, post-term pregnancy, maternal infections, maternal medical disorders, fetal growth restriction and fetal congenital abnormalities.1 A cross sectional study at a rural tertiary center in India showed that fetal growth restriction was the most common cause of stillbirths followed by hypertensive disorders, fetal congenital anomalies and maternal diabetes.6 In the year 2017, government of India issued a National Health Policy with a goal to reduce stillbirth rate to a “single digit” number by the year 2025.7 Stillbirth evaluation has always been difficult due to various reasons such as non-availability of services, religious and social beliefs and financial limitations. The Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network suggested postmortem examination, placental histology and fetal karyotype as a strong recommendation for evaluation of stillbirths.8 The causes of stillbirth differ in different parts of the world and are affected by poverty social factors and type of antenatal and intrapartum care. The objective of this study was to evaluate the etiology and risk factors for stillbirths.

Methods

This was a retrospective observational study at a private, tertiary perinatal institute, in Southern India from January 2010 to December 2015. All singleton births with a gestational age more than 24weeks and birth weight more than 500gm were included. Stillbirth was defined as a child born after 24weeks of pregnancy who did not breathe or show any signs of life after birth. Data was retrieved from the hospital electronic medical records. Risk factors were derived from maternal characteristics, past medical history, pregnancy complications, intrapartum details and fetal characteristics. The information was obtained on 18 risk factors; age, parity, body mass index (BMI), booking status, preexisting diabetes, hypertension, renal, cardiac, connective tissue disease and epilepsy. Pregnancy related complications such as hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, gestational diabetes, maternal infections, antepartum haemorrhage or acute fatty liver of pregnancy were noted. Fetal characteristics that were collected were gender, gestational age, birth weight and the growth centile at birth. The institute has a policy of screening for fetal growth restriction, and cardiotocography in labour. Small for gestational age fetuses were diagnosed on the basis of birth weight below the 10th centile for gestational age, using the institutional normograms.9,10 All women were subjected to universal screening for gestational diabetes with OGTT based on IADPSG criteria.11 For hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, the ACOG guideline developed by Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy was used.12 The findings from the placental histopathological examination and fetal autopsy were collected. Clinically relevant maternal laboratory tests like syphilis, TORCH (Toxoplasma, Rubella, Cytomegalovirus, Herpes Simplex Virus I and II), antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APLA), glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1C), and Kleihaeur-Betke (KB) test were a part of stillbirth evaluation protocol. The relevant condition at death (ReCoDe) classification was used to classify stillbirths.13 Maternal consent was obtained for use of data at the time of booking, and confidentiality was maintained as per institutional protocol. The primary outcome was to explore the incidence of stillbirths and its association with the risk factors. The secondary outcome was to apply ReCoDe classification to identify cause of stillbirth.

Statistical analysis

All the categorical variables were reported as frequency (percentage) and continuous variables as mean (SD). The contribution of demographic, medical risk factors that can be ascertained at the booking visit together with those that becomes apparent as pregnancy advances were analyzed. Poisson regression models were used to obtain unadjusted relative risks for still births. Multivariable Poisson regression was then performed taking the variables which were found significant in the univariate Poisson regression analysis to check the association of each independent variable with stillbirth. The independent variables included in the model were maternal age, BMI, parity, pre-existing diabetes, hypertension, preeclampsia, and cardiac, renal, connective disease complicating pregnancy, sex of fetus, growth pattern and infections in pregnancy. The analysis was done using Stata 14.0.

Results

The study period had 40,374 singleton births with 436 stillbirths, giving an incidence of 10.79/1000 births of more than 24weeks of pregnancy. For international comparisons, we had 314 stillbirths out of 40,190 with an incidence of 7.81/1000 births of more than 28weeks pregnancy.1Referrals were responsible for 57.1% (249) while the remaining 187 were in women who had booked for antenatal care and delivered at the institute. The stillbirth rate in booked population was 4.86/1000(187/ 38477) births.

Univariate analysis

Table 1 lists the Poisson regression model, with significant factors shown in univariate analysis. Maternal age more than 35years, parous women with more than 3 births, referral status, chronic hypertension, renal and cardiac disease were significant risk factors. Advanced maternal age pregnant women were 1.60(95% CI 1.12- 2.29) times more at risk of stillbirth compared to 25-29years. Women with 3 and more pregnancies had 1.7(95% CI 1.12- 2.59) times more risk of still birth. Referred women had relative risk of 24.16(95% CI 19.99, 29.20) to have stillbirth compared to booked population. BMI was not found to be significantly associated with still birth.

Risk factors |

Live births(AB) No(%) |

Stillbirths |

Rate per 1000 births |

Univariate analysis relative risk |

Multivariate analysis relative risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Age(in years) |

|||||

Less than 20 |

536(1.3) |

3(0.7) |

5.56 |

0.55(0.18-1.72) |

0.40(0.13-1.25) |

20-24 |

8489(21) |

101(23.2) |

11.75 |

1.16(0.91-1.47) |

0.96(0.76-1.21) |

25-29 |

19829(49.1) |

203(46.7) |

10.13 |

Reference |

|

30-34 |

9391(23.3) |

93(21.4) |

9.81 |

0.97(0.76-1.24) |

0.93(0.73-1.18) |

≥35 |

2127(5.3) |

35(8) |

16.19 |

1.60(1.12-2.29) |

1.13(0.80-1.59) |

Parity |

|||||

0 |

23045(57.1) |

263(60.5) |

11.28 |

1.19(0.96-1.49) |

0.94(0.76-1.17) |

1 |

12042(29.8) |

115(26.4) |

9.46 |

Reference |

|

2 |

3633(9) |

30(6.9) |

8.19 |

0.87(0.58-1.29) |

0.85(0.57-1.25) |

≥3 |

1649(4.1) |

27(6.2) |

16.11 |

1.70(1.12,2.59) |

1.40(0.95-2.06) |

BMI |

|||||

Less than 18.5 |

1406(3.5) |

8(3.9) |

5.66 |

1.06(0.5-2.19) |

|

18.5-24.9 |

14112(35.6) |

76(37.4) |

5.36 |

Reference |

|

25-29.9 |

15104(38.1) |

66(32.5) |

4.35 |

0.81(0.58-1.53) |

|

30-34.9 |

6804(17.2) |

38(18.7) |

5.55 |

1.04(0.70-1.53) |

|

≥35 |

2180(5.5) |

15(7.4) |

6.83 |

1.28(0.73-2.22) |

|

Booking status |

|||||

Booked |

38477(95.3) |

187(42.9) |

4.86 |

Reference |

|

Referral |

1882(4.7) |

249(57.1) |

116.84 |

24.16(19.9- 29.20) |

4.59(3.57-5.89) |

Hypertension in pregnancy |

|||||

No |

36067(98.2) |

234(94) |

6.44 |

Reference |

|

Pre-existing H |

654(1.8) |

15(6) |

22.42 |

3.48(2.06- 5.86) |

1.03(0.64-1.64) |

Gestational Hypertension |

1675(4.4) |

23(8.9) |

13.54 |

2.10(1.37-3.22) |

0.87(0.58-1.32) |

Preeclampsia |

1847(4.9) |

152(39.4) |

76.19 |

11.82(9.64-14.50) |

1.21(0.95-1.53) |

Eclampsia |

122(0.3) |

12(4.9) |

89.55 |

13.89(7.77-24.82) |

1.16(0.64-2.11) |

Diabetes complicating pregnancy |

|||||

No |

32186(84.6) |

385(93.7) |

11.82 |

Reference |

|

Pre-existing diabetes |

796(2.0) |

14(3.2) |

17.28 |

1.47(0.86-2.51) |

|

Gestational diabetes |

7386(18.3) |

37(8.5) |

4.99 |

0.425(0.30-0.60) |

|

Hypothyroid |

|||||

No |

32983(81.9) |

371(85.09) |

11.09 |

Reference |

|

Yes |

7277(18.1) |

65(14.9) |

8.85 |

0.80(0.61- 1.04) |

|

Epilepsy |

|||||

No |

40073(99.3) |

433(99.3) |

10.69 |

Reference |

|

Yes |

297(0.7) |

3(0.7) |

10 |

0.94(0.30- 2.91) |

|

Cardiac disease |

|||||

No |

40101(99.3) |

424(97.2) |

10.46 |

Reference |

|

Yes |

273(0.7) |

12(2.8) |

42.1 |

4.02(2.27- 7.14) |

1.60(0.94-2.74) |

Chronic kidney disease |

|||||

No |

40261(99.7) |

428(98.2) |

10.51 |

Reference |

|

Yes |

101(0.3) |

8(1.8) |

7.92 |

6.98(3.47- 14.04) |

1.52(0.84-2.74) |

Chronic liver disease |

|||||

No |

40312(99.9) |

436(100) |

|||

Yes |

57(0.1) |

0(0) |

0 |

||

Connective tissue disease |

|||||

No |

40021(99.1) |

429(98.4) |

10.6 |

Reference |

|

Yes |

350(0.9) |

7(1.6) |

19.6 |

1.85(0.88- 3.90) |

|

HIV positive |

|||||

No |

40201(99.6) |

433(99.3) |

10.66 |

Reference |

|

Yes |

169(0.4) |

2(0.5) |

11.7 |

1.10(0.28- 4.37) |

|

Infection - Hepatitis |

|||||

No |

40356(99.96) |

433(99.3) |

10.62 |

Reference |

|

Yes |

14(0.04) |

2(0.5) |

125 |

11.78(3.21- 43.20) |

1.81(0.53-6.24) |

Infection – Leptospira |

|||||

No |

40366(99.99) |

434(99.8) |

10.64 |

Reference |

|

Yes |

4(0.01) |

1(0.2) |

200 |

18.8(3.25- 108.80) |

0.79(0.09-6.96) |

Acute fatty liver of pregnancy |

|||||

No |

40356(100) |

429(98.4) |

10.51 |

Reference |

|

Yes |

18(0.00) |

7(1.6) |

280 |

26.62(14.1- 50.26) |

3.41(1.53-7.58) |

Antepartum haemorrhage |

|||||

No |

39644(98.2) |

390(89.4) |

9.74 |

Reference |

|

Yes |

730(1.8) |

46(10.6) |

59.27 |

6.09(4.48-8.26) |

1.52(1.14-2.03) |

Fetal characteristics |

|||||

Gender |

|||||

Male |

20628(51.2) |

221(50.7) |

10.6 |

Reference |

|

Female |

19676(48.8) |

212(48.6) |

10.6 |

1.006(0.83- 1.21) |

|

Growth pattern |

|||||

SGA |

3849(9.5) |

160(36.9) |

39.91 |

5.17(4.23 - 6.30) |

2.57(2.09-3.17) |

AGA |

31989(79.4) |

249(57.4) |

7.71 |

Reference |

|

LGA |

4474(11.1) |

25(5.8) |

5.55 |

0.719(0.48- 1.09) |

0.74(0.49-1.12) |

Birth weight in kg |

|||||

N= 40371 |

N = 436 |

||||

Mean(SD) |

2.92(0.63) |

1.42(0.86) |

|||

Gestational age at delivery |

|||||

>37weeks |

34804(86.2) |

66(15.1) |

1.89 |

Reference |

|

< 37weeks |

5567(13.8) |

370(84.9) |

62.32 |

32.93(25.34 - 42.78) |

14.32(10.38-19.76) |

Table 1 Risk factors for stillbirths and its associations

Pregnancy complications that were found to be risk factors for stillbirth were all categories of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, maternal infections and acute fatty liver of pregnancy. The relative risk was higher for gestational hypertension (RR 2.101; 95% CI 1.369-3.22), preeclampsia (RR 11.82; 95% CI 9.637-14.497) and worse for eclampsia (RR 13.89; 95% CI 7.77-24.815). Hypothyroidism, epilepsy and gestational diabetes were not found to have an association. Maternal infections like hepatitis, leptospira leading to multi-organ dysfunction were found to have high relative risks, although the numbers were small. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy is a known risk factor for stillbirths and was found to be the same in this series. The diagnosis of acute fatty liver of pregnancy was not always made through immune markers, and can possibly have hemolytic uremic syndrome, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura as its differential diagnosis for they mimic each other closely. Abruptio placenta was the leading placental cause of stillbirths, at all gestational ages. Women with antepartum haemorrhage had 6.09(95% CI 4.48 – 8.26) times more risk of having stillbirths compared to those who did not.

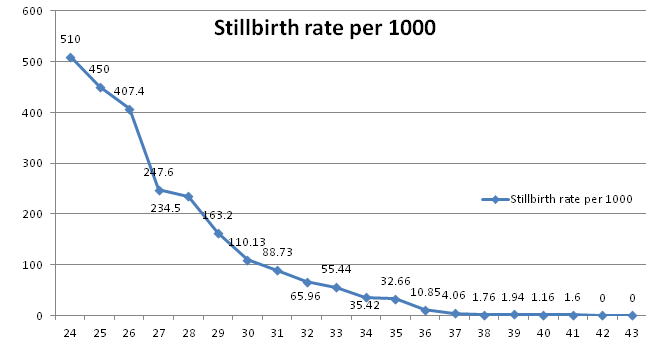

Fetal factors had fetal growth restriction as a major cause of stillbirths (RR 5.16, 95% CI 4.23–6.30). This causative factor remained in the top three causes of stillbirths in term and preterm birth categories. It was responsible for 27.8% of stillbirths in booked women after excluding referrals. Gestational age based stillbirth rate show an expected decline with increasing age, with lowest being at 40weeks and starting to rise at 41weeks (Figure 1). The limits of viability during the study period were 26weeks, 750gm and hence the fetal stillbirth rates were very high for babies less than 28weeks of pregnancy and less than 1000gm birth weight (Table 5). Gender was not found to have association with stillbirth.

Multivariate analysis

When compared to booked women, referred had 4.59(3.57- 5.89) times more risk of having still birth after adjusting for other factors. Women with AFLP have 3.41(95% CI 1.53- 7.58) times more risk to have stillbirths when compared to their counter parts. Antepartum haemorrhage with a relative risk of 1.52(95% CI 1.14-2.03) was also found to be significant factor. Small for gestational fetuses had 2.57(95% CI 2.09- 3.17) times increased risk as compared to average for gestational age fetuses. Women who had preterm delivery were at risk of stillbirth by 14.32(95% CI 10.38-19.76) times. Age, parity, hypertension, diseases like cardiac disease, chronic kidney disease and infections like hepatitis and leptospira lost their significance when adjusted for other factors. Majority were antepartum stillbirths (427, 97.04%) withonly nine intrapartum deaths (2.06%). Induction of labour was the most important risk factor for these intrapartum deaths (5 out of 9). Six of these were term pregnancies. Cause of intrapartum deaths was asphyxia in four, uterine rupture in two, lethal congenital anomalies in two and sepsis in one. The induction of labour protocol had PGE1 analogue Misoprostol (25mcg) through the study period.

The ReCoDe classification based etiological factors are shown in Table 2 & 3. ReCoDe classification was used to analyze the cause for stillbirths. Most common is fetal growth restriction in 124(27.9%) followed by no relevant condition identified in 92(20.7%). Among maternal causes Hyperetension complicating pregnancy contributed to stillbirths in 60(13.5%) and maternal diabetes was identified in 13(2.9%) cases. Next common cause is abruption placenta which leads to fetal demise in 53(11.9%) cases. The analysis was repeated for different gestational categories (extreme preterm, preterm and term) and also in booked population. We found that stillbirth rate was the highest in preterm group (28-36weeks gestational age n=249,57.1%) followed by extreme preterm (less than 28weeks n=121,27.7%) and was the least (n=36,15.1%) in term group (≥37weeks).The leading cause for stillbirth differs based on gestational age. The major causes for less than 28weeks stillbirths were hypertensive disorders(36,29.7%), fetal growth restriction(26, 21.48%) and cervical incompetence/preterm premature rupture of membranes (19, 15.7%). Stillbirths were highest in 28-36weeks gestational age group, and here, fetal growth restriction was seen in 36.1%, abruptio placenta 16.8% and in 15.6% cases, no relevant condition was identified. The term stillbirths had unexplained as the largest group (17, 25.75%), followed by diabetes (11, 16.6%) and fetal growth restriction (8, 12.12%). Unexplained deaths with no relevant condition identified were 56 (12.8%). Only 10(17.85%) consented to autopsy, 29(17.85%) had a placental HPE. Evaluation of this group showed fetal thrombotic vasculopathy as the most common placental lesion in 8(27.58%), antiphospholipid syndrome in 6(10.7%) and three had significant autopsy findings.

Code |

ReCoDe condition at birth |

Total (N=436) n,% |

Booked population stillbirths (N=187)n,% |

|---|---|---|---|

A |

FETUS RELATED |

||

A 1 |

Lethal congenital anomalies |

16(3.66) |

10(5.34) |

A 2 |

Infection |

1(0.22) |

1(0.53) |

A 3 |

Non immune hydrops |

1(0.22) |

0 |

A 4 |

Isoimmunization |

4(0.91) |

3(1.60) |

A 5 |

Feto-maternal haemorrhage |

1(0.22) |

0(0.53) |

A 6 |

Twin to twin transfusion |

0 |

0 |

A 7 |

Fetal growth restriction |

123(28.2) |

52(27.8) |

B |

UMBILICAL CORD RELATED |

||

B 1 |

Prolapse |

2(0.45) |

1(0.53) |

B 2 |

Constricting loop |

4(0.91) |

3(1.60) |

B 3 |

Velamentous insertion |

1(0.22) |

0 |

B 4 |

Others |

4(0.91) |

2(1.06) |

C |

PLACENTA RELATED |

||

C 1 |

Abruption |

53(12.1) |

14(7.48) |

C 2 |

Placenta praevia |

2(0.45) |

2(1.06) |

C 3 |

Vasa praevia |

0 |

0 |

C 4 |

Placental insufficiency / infarction |

2(0.45) |

0 |

D |

AMNIOTIC FLUID |

||

D 1 |

Chorio-amnionitis |

7(1.60) |

2(1.06) |

D 2 |

Oligohydramnios |

2(0.45) |

0 |

D 3 |

Polyhydramnios |

3(0.68) |

3(1.60) |

E |

UTERUS RELATED |

||

E 1 |

Rupture |

6(1.37) |

4(2.13) |

E 2 |

Uterine anomalies |

5(1.14) |

4(2.13) |

E3 |

Others |

19(4.35) |

10(5.34) |

F |

MATERNAL DISEASE |

||

F 1 |

Diabetes |

27(6.1) |

17(9.09) |

F 3 |

Essential hypertension |

3(0.68) |

1(0.53) |

F 4 |

Hypertensive disease in pregnancy |

67(15.3) |

16(8.55) |

F 5 |

Lupus or antiphospholipid antibody syndrome |

2(0.45) |

2(1.06) |

F 6 |

Cholestasis |

1(0.22) |

1(0.53) |

F8 |

Infection |

5(1.14) |

1(0.53) |

F9 |

Others |

14(3.2) |

3(1.60) |

G |

INTRAPARTUM |

||

G 1 |

Intrapartum asphyxia |

4(0.91) |

4(2.13) |

G2 |

Birth Trauma |

0 |

0 |

I |

UNCLASSIFIED |

||

I 1 |

No relevant condition identified |

56(12.8) |

30(16.04) |

I 2 |

No information available |

0 |

0 |

Table 2 ReCoDe Classification of Stillbirths)

Code |

ReCoDe condition at birth |

Less than 28weeks N=121 |

28-36weeks N=248 |

More than 37weeks N= 66 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

A |

FETUS RELATED |

|||

A 1 |

Lethal congenital anomalies |

3(2.47) |

7(2.82) |

6(9.0) |

A 2 |

Infection |

0 |

1(0.4) |

0 |

A 3 |

Non immune hydrops |

0 |

1(0.4) |

0 |

A 4 |

Isoimmunization |

1(0.82) |

3(1.2) |

0 |

A 5 |

Feto-maternal haemorrhage |

0 |

0 |

1(1.51) |

A 6 |

Twin to twin transfusion |

0 |

0 |

0 |

A 7 |

Fetal growth restriction |

26(21.4) |

89(35.8) |

8(12.12) |

B |

UMBILICAL CORD RELATED |

|||

B 1 |

Prolapse |

0 |

1(0.4) |

1(1.51) |

B 2 |

Constricting loop |

1(0.82) |

1(0.4) |

2(3.03) |

B 3 |

Velamentous insertion |

0 |

0 |

1(1.51) |

B 4 |

Others |

0 |

4(1.61) |

0 |

C |

PLACENTA RELATED |

|||

C 1 |

Abruption |

7(5.78) |

42(16.9) |

4(6.06) |

C 2 |

Placenta praevia |

2(1.65) |

0 |

0 |

C 3 |

Vasa praevia |

0 |

0 |

0 |

C 4 |

Placental insufficiency / infarction |

0 |

1(0.4) |

1(1.51) |

D |

AMNIOTIC FLUID |

|||

D 1 |

Chorio-amnionitis |

3(2.47) |

3(1.2) |

1(1.51) |

D 2 |

Oligohydramnios |

0 |

2(0.8) |

0 |

D 3 |

Polyhydramnios |

1(0.82) |

1(0.4) |

1(1.51) |

E |

UTERUS RELATED |

|||

E 1 |

Rupture |

1(2.47) |

4(1.61) |

1(1.51) |

E 2 |

Uterine anomalies |

2(1.65) |

3(1.2) |

0 |

E3 |

Others |

19(15.70) |

0 |

0 |

F |

MATERNAL DISEASE |

|||

F 1 |

Diabetes |

2(1.65) |

14(5.64) |

11(16.6) |

F 3 |

Essential hypertension |

1(0.82) |

2(0.8) |

0 |

F 4 |

Hypertensive disease in pregnancy |

36(29.7) |

26(10.4) |

5(7.57) |

F 5 |

Lupus or antiphospholipid antibody syndrome |

1(0.82) |

0 |

1(1.51) |

F 6 |

Cholestasis |

0 |

1(0.4) |

0 |

F8 |

Infection |

0 |

4(1.61) |

1(1.51) |

F9 |

Others |

2(1.65) |

12 |

1(1.51) |

G |

INTRAPARTUM |

|||

G 1 |

Intrapartum asphyxia |

0 |

1(0.4) |

3(4.54) |

G2 |

Birth Trauma |

0 |

0 |

0 |

I |

UNCLASSIFIED |

|||

I 1 |

No relevant condition identified |

13(10.74) |

25(10.08) |

17(25.75) |

I 2 |

No information available |

0 |

|

0 |

Table 3 ReCoDeclassification in different gestational age groups

Gestational age in weeks |

Total births(N=40374) |

Stillbirths(N=436) |

SB rate per 1000 |

|---|---|---|---|

24 |

24 |

25 |

510 |

25 |

33 |

27 |

450 |

26 |

48 |

33 |

407.4 |

27 |

79 |

26 |

247.6 |

28 |

124 |

38 |

234.5 |

29 |

164 |

32 |

163.2 |

30 |

202 |

25 |

110.13 |

31 |

267 |

26 |

88.73 |

32 |

354 |

25 |

65.96 |

33 |

460 |

27 |

55.44 |

34 |

708 |

26 |

35.42 |

35 |

1007 |

34 |

32.66 |

36 |

2096 |

23 |

10.85 |

37 |

6488 |

25 |

4.06 |

38 |

10764 |

19 |

1.76 |

39 |

9218 |

18 |

1.94 |

40 |

7709 |

9 |

1.16 |

41 |

624 |

1 |

1.6 |

42 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

43 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

Table 4 Gestational age based stillbirth rate

Birth weight category |

Total births(N = 40374) |

Stillbirths(N = 438) |

SB rate per 1000 |

|---|---|---|---|

Less than 999gm |

374 |

188 |

334 |

1000 to 1499gm |

831 |

67 |

74.6 |

1500 to 1999gm |

1292 |

59 |

43.6 |

2000 to 2499gm |

4390 |

45 |

10.14 |

2500 to 2999gm |

13589 |

49 |

3.59 |

More than 3000gm |

19898 |

30 |

1.5 |

Table 5 Birth weight distribution of stillbirths

Discussion

There is regional variation in stillbirth rates. There is variation seen from one institute to another in a particular region too. The current worldwide stillbirth rate is 18.9 per 1000 births. The stillbirth rate in India is 22 per 1000 births and varies from 20 to 66 per 1000 births in different states. In this study, the incidence of stillbirth was found to be 12.3 per 1000 live births. The incidence was low in our study in contrary to other Indian studies done by Neetu Singh14 (SBR was 40 per 1000) and Bellad et al.15 (SBR of 43 per 1000 births).

Systemic reviews16 have shown that older mothers have higher risk of stillbirths. A Cross sectional analysis17 has shown that para 3 or more mothers are at risk of stillbirths, though in this study it was not seen. Population based study18 showed obesity as risk factor for stillbirth which is contrary to our analysis. When compared to booked women, referral ones had 4.59times more risk of having a stillbirth after adjusting for other risk factors. Fetal growth restriction was one of the major cause of stillbirths (52, 27.8%) in referral women. Women who had preterm delivery were at increased risk of stillbirth by 14.32(95% 10.38-19.76) times. Gender of the fetus was not found to have any association with stillbirth.

Based on ReCoDe classification the commonest cause for stillbirths in this study was FGR (27.9%), followed by no relevant condition identified (unexplained) in 20.7%. Hypertension complicating pregnancy contributed to stillbirths in 60 (13.5%) and maternal diabetes was identified in 13(2.9) cases. Population based cohort study by Jason Gardosi et al. published in 2013 showed stillbirth rate of 5.82 per 1000 (excluding fetal anomalies and multiple pregnancies) with fetal growth restriction as largest category of stillbirth 1129(43%) followed by no relevant condition identified in 398(15.2%). In this population based study by Gardosi et al., FGR contributed to more number of stillbirths as compared to our study.18 Screening for fetal growth restriction and identification with timely intervention has been an accepted strategy for reducing stillbirth rate.19

Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy leading to stillbirth washigh in our study in contrast to others which showed rate of 9.2%14 and 10.81%.8 The relative risk was higher for gestational hypertension and preeclampsia and worse for eclampsia. Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy were associated with fetal growth restriction; they require delivery for maternal complications so they were delivered earlier when compared to normotensive women with FGR. Rate and cause of stillbirths differs based on the gestational age. In this study, almost 57% of stillbirths were between 28-36weeks, one fourth were below 28weeks and 15% in term pregnancies. Between 24-27weeks, the most common causes of stillbirth were hypertensive diseases in pregnancy (29.7%), fetal growth restriction (20%) and no relevant condition was identified in 19%. In Hypertensive disease in pregnancy 50% were terminated in view of deteriorating maternal condition. Fetal growth restriction was the second common cause, of which 73% cases were referrals. However, other studies such as Stromdal et al.20 showed placental insufficiency (23%) as the common cause in this gestational age group, followed by infection and abruption. Fretts21 analysis showed infection as the common cause, next common cause was abruption and anomalies.

Between 28-36weeks, the most common cause of stillbirths in this study is that of fetal growth restriction (36%), followed by abruption (16%). Amongst fetal growth restriction, majority were referrals (58%). This clearly means that considering gestational age and birth weight, these babies would have been salvaged if they were identified in antenatal period, puton surveillance and delivered in time. An analysis of stillbirths was published by Liu LC et al.22,23 in 2013 which stated that in 28-36weeks group, umbilical cord pathology was the most common cause of stillbirth accounting to one-third of cases. This was followed by maternal medical condition (24.1%) and 14.8% cases remained unexplained. Frets et al.23 published etiology of stillbirth in 2005, which revealed that in this group, 26% of cases were unexplained, 19% due to fetal growth restriction and placental abruption contributed to 18% of cases. Abruption is a known risk factor for stillbirth at all gestational ages in these studies, which emphasis the need for immediate and thorough need for evaluation of antepartum hemorrhage.

No relevant condition was identified for term stillbirths in 50% of cases in this series. The rest were fetal growth restriction (7%), lethal anomalies (9%) and abruption (6%). In the study by Frets et al, 40% of stillbirths remained unexplained, 14% were due to fetal growth restriction and 12% were because of abruption. Stormdal Bring et al.22 showed that at term, the leading causes of stillbirth were infection (26%), fetal growth restriction (20%) and 14.5% were unexplained. The stillbirth collaborative research group network writing group analysed8 causes of stillbirth in 663 cases, found that placenta had highest proportion of positive results(52.3% [268]; 95% CI, 47.9%-56.7%), perinatal post-mortem has positive findings in 161 cases(31.4% 95% CI, 27.5 – 35.7%) and karyotype was abnormal in 32 of the 357 successful studies(9.0%; 95% CI,6.3-12.5%).The remaining clinical tests were positive in only 0.4–4.8% of stillbirths. Our number of 50% of unexplained stillbirth may be an over-estimate because most of the times, our hands are tied with regard to investigations since the parents do not consent for autopsy, karyotype or placental histopathology due to financial and social factors.

Eleven diabetes related deaths formed 16.6% of term stillbirths (Table 3), even though it was not found to be a statistically significant risk factor. Screening being universal in India, the emphasis should now be on monitoring protocols for these women, and support systems for better compliance. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP) is a known risk factor for stillbirths,retrospective data from China24 showed 13% stillbirth rate, similarly our data showed women with AFLP have 3.41%955CI 1.53-7.58) times more risk for stillbirths when compared to their counterparts.

Intrapartum stillbirths were few in this study, but were significant in bringing a change in the fetal monitoring policy of the institute. The need for one to one monitoring in low risk mothers, with continuous cardiotocography in high risk mothers are accepted guidelines but are sometimes difficult to implement due to multiple factors.25 There were case reports26 of uterine rupture following induction with misoprostol. Our series had two uterine ruptures following induction with misoprostol. This study has a few shortcomings. This is aninstitutional data, where tertiary care is offered, so this data cannot be extrapolated to the community. Fetal karyotype, placental histopathology and autopsy were not done for all stillbirths because of lack of social acceptance of these investigations in the community. Financial constraint was also one of the factors that compelled the couples to refuse these investigations.

Conclusion

Stillbirths replace joy with bereavement. This study emphasizes the need for screening and appropriate management for fetal growth restriction. Identification of risk factors, improving detection of FGR, appropriate and timely intervention in pre-eclampsia may reduce stillbirths. Protocols for uniformity of antenatal and intrapartum care are essential to reduce stillbirths. There is an urgent need for the world to focus on these preventable deaths.

Acknowledgements

I acknowledge my colleagues at Fernandez Hospital and especially our director DrEvita Fernandez for constant support and encouragement.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Contribution of authorship

SDK, NA, ARG, TS conceived of, designed, analyzed and wrote the review. DN, HBP analyzed the data.

Details of ethics approval

No ethical approval was required as this is a retrospective observational study

Funding

No funding was received.

References

- World Health Organization WHO. Maternal, newborn, childhood and adolescent health. 2016.

- Blencowe H, Cousens S, Jassir FB, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2015, with trends from 2000: a systematic analysis. The Lancet Global Health. 2016;4(2):e98‒e108.

- Lawn JE, Blencowe H, Waiswa P, et al. Stillbirths: rates, risk factors, and acceleration towards 2030. The Lancet. 2016;387(10018):587‒603.

- Bhutta ZA, Das JK, Bahl R, et al. Can available interventions end preventable deaths in mothers, newborn babies, and stillbirths, and at what cost? The Lancet. 2014;384(9940):347‒370.

- World Health Organization WHO. Health Topics, Risk factors. 2014.

- Aminu M, Unkels R, Mdegela M, et al. Causes of and factors associated with stillbirth in low‐and middle‐income countries: a systematic literature review. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2014;121(suppl 4):141‒153.

- National health policy. Ministry of health and family welfare, Government of India. 2017.

- Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network Writing Group. Causes of death among stillbirths. JAMA. 2011;306(22):2459‒2468.

- Kandraju H, Agrawal S, Geetha K, et al. Gestational age-specific centile charts for anthropometry at birth for South Indian infants. Indian pediatrics. 2012;49(3):199‒202.

- Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. The investigation and management of the small-for-gestational-age fetus (Green-top Guideline 31). 2nd ed. London: RCOG. 2013.

- Duran A, Sáenz S, Torrejón MJ, et al. Introduction of IADPSG criteria for the screening and diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus results in improved pregnancy outcomes at a lower cost in a large cohort of pregnant women: the St. Carlos Gestational Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(9):2442‒2450.

- Hypertension in Pregnancy. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2013.

- Gardosi J, Kady SM, McGeown P, et al. Classification of stillbirth by relevant condition at death (ReCoDe): population based cohort study. BMJ. 2005;331(7525):1113‒1117.

- Singh N, Pandey K, Gupta N, et al. A retrospective study of 296 cases of intra uterine fetal deaths at a tertiary care centre. International Journal of Reproduction, Contraception, Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2013;2(2):141‒146.

- Bellad MB, Srividhya K, Ranjit K, et al. Factors associated with perinatal mortality: a descriptive observational study. Journal of South Asian Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2010;2(1):49‒51.

- Flenady V, Koopmans L, Middleton P, et al. Major risk factors for stillbirth in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The lancet. 2011;377(9774):1331‒1340.

- Bai J, Wong FW, Bauman A, et al. Parity and pregnancy outcomes. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2002;186(2):274‒278.

- Gardosi J, Madurasinghe V, Williams M, et al. Maternal and fetal risk factors for stillbirth: population based study. BMJ. 2013;346:f108.

- Clifford S, Giddings S, Southam M, et al. The Growth Assessment Protocol: a national programme to improve patient safety in maternity care. MIDIRS Midwifery Digest. 2013;23(4):516‒523.

- Stormdal Bring H, HulthénVarli IA, Kublickas M, et al. Causes of stillbirth at different gestational ages in singleton pregnancies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014;93:86–92.

- Fretts RC. Etiology and prevention of stillbirth. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2005;193(6):1923‒1935.

- Liu LC, Huang HB, Yu MH, et al. Analysis of intrauterine fetal demise—A hospital-based study in Taiwan over a decade. Taiwanese Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2013;52(4):546‒550.

- Liu LC, Wang YC, Yu MH, et al. Major risk factors for stillbirth in different trimesters of pregnancy—A systematic review. Taiwanese Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2014;53(2):141‒145.

- Zhang YP, Kong WQ, Zhou SP, et al. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy: a retrospective analysis of 56 cases. Chinese medical journal. 2016;129(10):1208‒1214.

- National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health. Intrapartum care - Care of healthy women and their babies during childbirth. Guideline No 190. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2014.

- Thomas A, Jophy R, Maskhar A, et al. Uterine rupture in a primigravida with misoprostol used for induction of labour. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2003;110(2):217‒218.