Volume : 1 | Issue : 1

Case Report

Selective thoracoscopic intercostal block through a transbronchial aspiration needle: an alternative analgesic tool for pain control after video-assisted thoracic surgery

Andres Obeso

Department of Thoracic Surgery, Heart & Vascular Institute, UAE

Received: February 03, 2018 | Published: March 22, 2018

Abstract

Video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) is a surgical procedure increasingly used to treat several thoracic diseases. Postoperative pain control is one of the mainstays for patient recovery. A proper analgesic management leads to faster recovery, reduce hospital stay and decreased possibility of postoperative complications. Even though different regional techniques have been reported, optimal post-operative analgesia after VATS remains controversial. Here we describe an alternative analgesic tool using a transbronchial aspiration needle for intraoperative thoracoscopic intercostal block. This technique allows selective intercostal block from the origin of the intercostal nerve, close to the costovertebral joint.

Keywords: anesthesia, pain, perioperative care, thoracoscopy, VATS

Introduction

Postoperative pain control is essential to achieve a faster recovery, reduce hospital length of stay and decrease the possibility of postoperative complications.1-2 Up to date, although different analgesic techniques have been described,3 no gold standard currently exists with respect to regional analgesia for Video Assisted Thoracic Surgery (VATS) procedures. Here, we present an alternative surgical tool using a transbronchial aspiration needle for selective intraoperative thoracoscopic intercostal block.

Technique

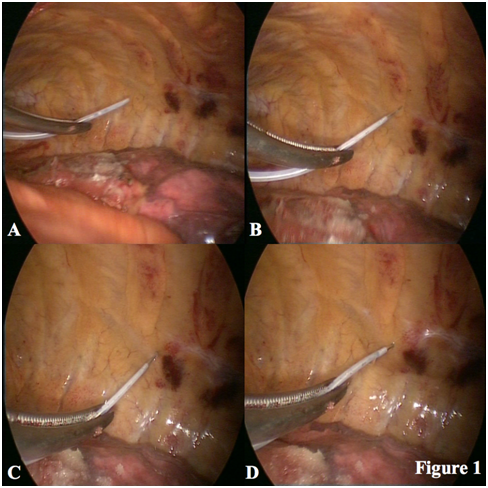

An 85-year-old man was referred to our Department for evaluation. Thoracic Computed Tomography scan revealed a 2.8 cm nodule in the apicoposterior bronchopulmonary segment of the left upper lobe. There were no enlarged hiliar and mediastinal lymph nodes. A Positron Emission Tomography scan showed increased Fluorodeoxyglucose uptake (SUV 12.6 g/ml) in the pulmonary nodule previously described. Pulmonary function test was normal (FEV1: 1680 cc, 77.6%; DLCO/VA: 98.2%). Once the preoperative evaluation was completed, the patient underwent surgery. Informed consent was signed previously. General anesthesia was induced, and endotracheal intubation was performed with double lumen tube. The patient was placed in lateral decubitus. Due to the longevity of the patient, minimally invasive thoracic surgery seemed to be the best approach to facilitate the postoperative recovery. Biportal VATS technique was performed. A 3 cm long utility incision was placed at the fifth intercostal space anteriorly and a 1 cm camera-port was made in the eighth intercostal space at the level of the posterior axillary line. Once left upper lobectomy and systematic lymphadenectomy was completed, we decided to perform a selective endoscopic intercostal blockade to achieve a good postoperative analgesia. We used a 22-gauge WangTM transbronchial aspiration needle (Figure 1). First, we introduced the closed-needle guided with a Rochester-Pean forceps through the utility incision. Once inside the chest, the needle was protracted and locked. Then, we identified the intercostal space that we wanted to infiltrate, and punctured the parietal pleural below the inferior margin of the rib, with the goal of placing the tip into the space containing the neurovascular bundle between the innermost intercostal muscles and the internal intercostal muscle. The best place to puncture is as close as possible to the origin of the intercostal nerve, about 1 or 2 cm from the costovertebral joint. Then the needle was advanced 4 mm and, following hemo-negative aspiration, we infiltrated 3 ml of Levobupivacaine 0.5%. Immediately we could see how the local anesthetic spreaded through the intercostal space. Finally, the needle was retracted and withdrawn. The process was repeated as the remaining levels of blockade, in this case 5th and 8th intercostals spaces. This internal anesthetic block was supplemented with intravenous and oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) every four hours during hospital stay. Postoperative course was uneventful, the pain was under control and the patient was discharged three days later.

Discussion

Thoracic surgical procedures are becoming less and less invasive over time. One of the main benefits of VATS is that it causes less postoperative pain than thoracotomy.4 This advantage leads to faster post-surgical recovery and shorter hospital stay.5 Furthermore, uniportal approach and the design of adapted thoracoscopic devices as flexibl.6-7 Hence, pain management should be adapted to this new situation since the less invasive is the approach, the more selective should be the analgesic technique used.

Up to date, different regional techniques have been described for control of postoperative pain after VATS such as thoracic epidural analgesia, paravertebral catheter, multilevel and single paravertebral block, intercostal catheter and internal or transthoracic intercostal nerve block.3 However, optimal post-operative analgesia after thoracoscopic procedures remains controversial. A systematic review published by Steinhorsdottir et al.8 in 2014 concluded that there is no gold standard for regional analgesia for VATS. In that review, thoracic Epidural Analgesia and especially Paravertebral Block showed some effect on pain scores but were often compared with an inferior analgesic treatment. Hence future randomized trials are necessary to determine the optimal analgesic method for minimally invasive thoracic surgery.

In this manuscript, it is described the use of a WangTM transbronchial aspiration needle as an alternative analgesic tool for selective thoracoscopic intercostal block. This is a flexible retractable needle to ensure safe access to the pleural cavity. It avoids puncturing accidentally the lung and thoracic vessels. Furthermore, clear catheters allow us for direct visualization to check hemo-negative aspiration. Finally, locking mechanisms assure needle stability when injecting. These three characteristics provide reliability, safety, comfortability and accuracy. Anyway, accidental puncture of the intercostal vessels should be avoided to prevent either intraoperative or postoperative bleeding. With this technique, we achieve a selective intercostal block from the origin of the intercostal nerve close to the costovertebral joint. Maybe this is the main advantage over transthoracic intercostal blockade in which the interposition of the scapula prevents easy access through the chest wall to the higher intercostal spaces posteriorly. On the other hand, the use of a selective intercostal block may avoid unwanted systemic effects of paravertebral block and thoracic epidural analgesia. Additionally, this thoracoscopic technique is technically easier to perform and cheaper compared with the last ones. However, the use of regional techniques alone may not be sufficient. Therefore, supplementary oral or intravenous NSAID should be additionally administered for pain control.

In conclusion, selective thoracoscopic intercostal block through a WangTM transbronchial aspiration needle is a safe, effective and easily reproducible technique. Despite its several advantages, further randomized prospective studies are necessary to analyze its effectiveness and support this analgesic technique. It is possible that coming years, new and specific analgesic devices will be developed and adapted for VATS.

Conflict of interest

none declared.

References

- Kavanagh BP, Katz J, Sendler AN. Pain control after thoracic surgery. A review of current techniques. Anesthesiology. 1994;81(3):737–754.

- Kehlet H. Acute pain control and accelerated postoperative surgical recovery. Surg Clin North Am. 1999;79(2):431–443.

- Mulder DS. Pain management principles and anesthesia techniques for thoracoscopy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1993;56(3):630–632.

- Landreneau RJ, Hazelrigg SR, Mack MJ, et al. Postoperative pain-related morbidity: video-assisted thoracic surgery versus thoracotomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1993;56(6):1285–1289.

- McKenna RJ, Houck W, Fuller CB. Video-assisted thoracic surgery lobectomy: experience with 1100 cases. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81(2):421–426.

- Tamura M, Shimizu Y, Hashizume Y. Pain following thoracoscopic surgery: retrospective analysis between single-incision and three-port video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;8:153.

- Jutley RS, Khalil MW, Rocco G. Uniportal vs standard three-port VATS technique for spontaneous pneumothorax: comparison of post-operative pain and residual paraesthesia. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005;28(1):43–46.

- Steinthorsdottir KJ, Wildgaard L, Hansen HJ, et al. Regional analgesia for video-assisted thoracic surgery: a systematic review. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;45(6):959–966.