Volume : 1 | Issue : 1

Case Report

It is a bile!

Ahmed Fayed,1 Mona Hassan2

1Mansoura Chest Hospital, Egypt

2Faculty of Dentistry, Mansoura University, Egypt

Received: July 04, 2018 | Published: July 25, 2018

Abstract

Bilothorax is a rare reported complication of hepatobiliary tree manipulation and can cause a great threat for life. We reported in this case a benign course of this problem without detection of obvious communication between peritoneal and pleural spaces and without peritonitis.

Keywords: bilothorax, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage, conservative management

Abbreviations

alanine transaminase (ALT), acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), aspartate transaminase (AST), celsius (oC), computerized tomography (CT), chest x ray (CXR), bicarbonate (HCO3), intercostal tube (ICT), international normalized ratio (INR), potassium (K), litre (L), millimetre mercury (mmhg), sodium (Na), partial pressure of carbon dioxide in blood (PaCO2), potential hydrogen (PH), percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD), partial pressure of oxygen in blood (SPO2)

Introduction

Known also as cholethorax, bilothorax is a rare described or seen cause of pleural effusion1 in which pleural fluid consists of a bile and is usually occurs after hepatic tumor or abscess rupture or traumatic hepatobiliary laceration.2,3 It can be a very serious cause of morbidity and mortality4 as bile have a strong corrosive effect and also a good soil for infection that can lead to ARDS with fatal course.2

Case description

A 59-year-old female with history of metastatic cholangiocarcinoma to liver and lung on 2nd line oral chemotherapy capecitabine (after failure of the 1st line therapy) and non-functioning common bile duct stent presented with epigastric pain, vomiting, diarrhoea and shortness of breath with lower back pain. In emergency room patient was in pain and jaundiced with Blood pressure 150/80 mmhg, heart rate 86 beat/minute, SPO2 98% on room air, temperature 37.4 oC, abdominal examination showed epigastric tenderness and ecchymosis, chest examination was unremarkable, AST 44, ALT 37, Bilirubin 13.5, alkaline phosphatase 560, albumin 2.5, Na. 129, K 3.2, creatinine 0.6, INR 1.2, PH 7.57, PCO2 24, HCO3 22.

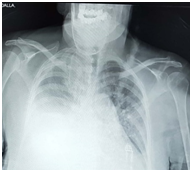

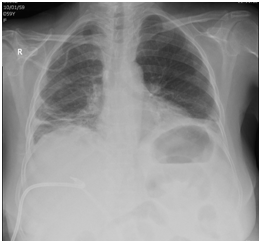

After 2 days a percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) was inserted by interventional radiologist but suspected to be leaked by internal medicine team after that and also patient started to be desaturated at night with SPO2 89% on room air with a right basal heterogeneous opacity and obliteration of costophrenic angle on chest x ray (CXR) (Figure 1) for which pulmonologist on call consulted and he advised for chest physiotherapy and hypertonic saline nebulization (he may thought of lung collapse) and patient kept on oxygen 5L by face mask keeping SPO2 at 95%.

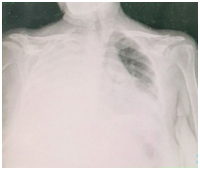

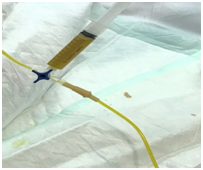

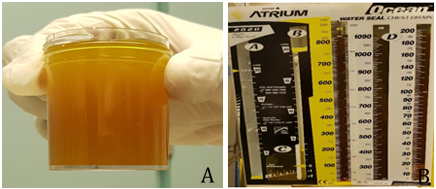

3 days later pulmonologist was consulted for more desaturation of the patient. Later on CXR, requested urgently by pulmonologist, showed massive right pleural effusion (Figure 2) for which a diagnostic thoracocentesis done which revealed yellow to brownish coloured fluid mostly bilious in nature (Figure 3) and a representative sample was sent for analysis and later on pleural fluid investigations results as following brownish turbid sample, WBCs 4500 mm3 with 95% neutrophils, no bacteria with few inflammatory cells in gram stain with no growth on culture and sensitivity, glucose 67 mg/dl, LDH 350 U/L (335 U/L in blood), albumin 1.8 G/dl (2.5 G/dl in blood), protein 3.0 G/dl (4.7 G/dl in blood) and amylase 29 U/L.

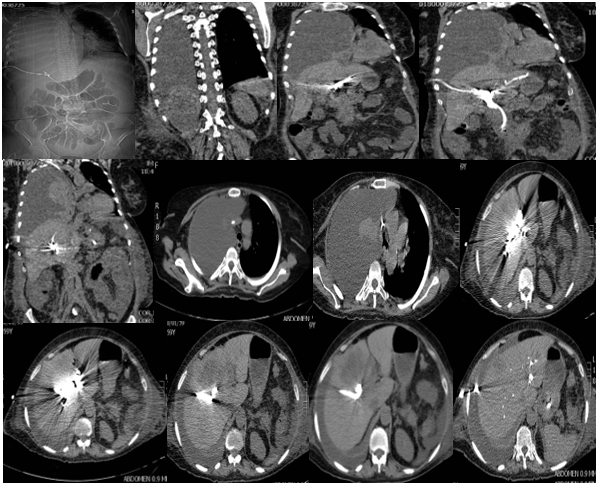

Urgent thoracic surgery consultation was done for intercostal tube (ICT) insertion, but strangely thoracic surgeon postponed the procedure for the next day waiting for computerized tomography (CT) of the abdomen and chest with contrast requested by oncologist to ensure about leakage from PTBD and commented on low thoracocentesis done by pulmonologist in eight spaces (he may have thought about iatrogenic biliary injury by pulmonologist!). CT chest and abdomen came later and reported by radiologist against any leakage (Figure 4).

ICT was inserted next day (after discussion with both thoracic surgeon and patient about the hazards of this condition and risk of postponed procedure) and drained through the next 48 hours about 3000 ml yellow brownish fluid (Figure 5).

Later on, ICT was removed after being sure about the functioning of abdominal drain with CXR post removal of ICT showed fully expanded lung (Figure 6) and oxygen saturation is 93% on room air. Patient then referred for her original facility to continue her management.

Discussion

Large volumes of intra-abdominal air, ascitic fluid or blood are capable of directly traversing the diaphragm through a congenital, traumatic, or erosive defects to enter the pleural space.5–7 Also, indirect routes as tissue sheaths of the oesophagus and great vessels8, via the lymphatics or transfer through gaps in the muscle fibres and bundles of the diaphragm were suggested.9,10

Because of the anatomical position of the liver directly under right hemidiaphragm, the right-sided bilothorax is the most frequently reported although left-sided bilothorax has been reported also.11 Spontaneous bilio‑pleural fistula can occur in patients with gall stones.12 Also, bile can reach directly bronchial tree very rarely by a broncho‑biliary fistula and results in bilioptysis.13

As the role that emphasise “fluid will follow the path of least resistance” the bilothoracic fistula only develops when intra-abdominal accumulation of bile is inadequately drained and no direct bilio‑pleural fistula and when the biliary system was adequately drained by an intra-abdominal tube, bile leakage into the pleural cavity ceased and the chest tube could be removed without recurrence of biltohorax3 and this is exactly what happened in our case.

Most cases of pleurobiliary fistula have been reported after hepatic abscess formation or biliary tract obstruction14 and in some rare cases result from abdominal trauma15 specially iatrogenic after percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage.16

Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) commonly used for obstructive jaundice and cholecystitis with a reported 0.5% of cases complicated by pleural effusion.16 Although lung injury can be easily avoided during PTBD with the use of ultrasonography or CT together with estimation of the extent of the pleural space prior to the procedure,17 the PTBD catheter may be mis-inserted through the pleural space as the liver is anatomically surrounded by the thoracic cavity.18,19 Also, bile leakage along the drain has been reported after PTBD as a late complication in 18.8%–21.7% of patients.20

Bile is a strong inflammatory stimulus due to both a direct corrosive effect on the pleural layers and also a very good soil for bacterial infection with empyema formation causing a therapeutic challenge for the clinicians.21,22 Moreover, bile is a fibrogenic agent that can cause fibrothorax for this any delay in drainage of pleural fluid can rapidly give rise to a permanent compromised lung function and also acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a rare but fatal complication that can be result from this condition.2

There is no much experience in treatment of bilothorax23 but early drainage of the bilious pleural fluid either by intercostal tube or pig‑tail catheter is the standard recommendation for the management2,24and if associated with infection, should be treated as same as pleural empyema.25 For bilio‑pleural fistula, usually the fistulous tract heals spontaneously without any surgical intervention.15,24

Conclusion

Although not a common problem and benign course of our case without peritonitis or residual morbidity till discharge, cholethorax should be suspected in any patient with respiratory manifestation with history of hepatobiliary manipulation or problem because of its fatal complications and morbidity. The course of this condition depends on the early diagnosis and careful care. Radiologist should take all measures to prevent lung injury or false insertion of catcher during PTBD due to intimate anatomical relation of the lung to liver.

References

- Basu S, Bhadani S, Shukla VK. A dangerous pleural effusion. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010;92(5):W53−54.

- Aydogan A, Erden ES, Akkucuk S, et. Cholethorax (bilious effusion in the thorax): an unusual complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Arch Iran Med. 2013;16(8):489.

- Hamers LAC, Bosscha K, van Leuken MH, et al. Bilothorax: A bitter complication of liver surgery. Case Rep Surg. 2013.

- Jenkinson MRJ, Campbell W, Taylor MA. Bilothorax as a rare sign of intra-abdominal bile leak in a patient without peritonitis. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2013;95(7):e12–e13.

- Meigs JV, Cass JW. Fibroma of the ovary with ascites and hydrothorax: with a report of seven cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1937;33(2):249–267.

- Pratt JH, Shamblin WR. Spontaneous hemothorax as a direct complication of hemoperitoneum. Ann Surg. 1968;167(6):867.

- Banyai AL, Jurgens GH. Accidental pneumothorax during pneumoperitoneum treatment. Am Rev Tuberculosis. 1940;(42):688.

- Rowe PH. Bilothorax-an unusual problem. J R Soc Med. 1989;82(11):687–688.

- Long AE. Hemothorax in relation to benign pelvic tumors. Calif Med. 1948;68(5):383.

- Kaya S, Hasanoglu C, Demirbas B, et al. An unusual complication of the surgery of pyloric stenosis: bilothorax. Chest. 2006;130(4):302S.

- Vink EE, Kröner A, Spronk PE. A Secondary Left-Sided Bilothorax after a Car Accident. NETHERLANDS SOC INTENSIVE CARE HORAPARK 9, EDE, 6717 LZ, NETHERLANDS; 2016.

- Cunningham LW, Grobman M, Paz HL, et al. Cholecystopleural fistula with cholelithiasis presenting as a right pleural effusion. Chest. 1990;97(3):751–752.

- Fröbe M, Kullmann F, Schölmerich J, et al. Bronchobiliary fistula associated with combined abscess of lung and liver. Med Klin Munich Ger. 2004;99(7):391–395.

- Oparah SS, Mandal AK. Traumatic thoracobiliary (pleurobiliary and bronchobiliary) fistulas: clinical and review study. J Trauma. 1978;18(7):539–544.

- Sheik-Gafoor MH, Singh B, Moodley J. Traumatic Thoracobiliary Fistula: Report of a Case Successfully Managed Conservatively, with an Overview of Current Diagnostic and Therapeutic Options. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 1998;45(4):819.

- Tsuyuguchi T, Takada T, Kawarada Y, et al. Techniques of biliary drainage for acute cholangitis: Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14(1):35–45.

- Sano A, Yotsumoto T. Bilothorax as a complication of percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2016;24(1):101–103.

- Gothlin J, Tranberg K. Complications of percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC). Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1973;(117):426–431.

- Suehiro M, Ishimura J, Fukuchi M. Detection of bile leakage into the thoracic cavity by hepatobiliary scintigraphy. Ann Nucl Med. 1991;5(4):167–169.

- Garcarek J, Kurcz J, Guzinski M, et al. Ten years single center experience in percutaneous transhepatic decompression of biliary tree in patients with malignant obstructive jaundice. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2012;21(5):621–632.

- De Luca D, Minucci A, Zecca E, et al. Bile acids cause secretory phospholipase A2 activity enhancement, revertible by exogenous surfactant administration. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(2):321–326.

- Lee M-T, Hsi S-C, Hu P, et al. Biliopleural fistula: a rare complication of percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage. World J Gastroenterol WJG. 2007;13(23):3268.

- Cooper AZ, Gupta A, Odom SR. Conservative management of a bilothorax resulting from blunt hepatic trauma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93(6):2043–2044.

- Singh B, Moodley J, Sheik-Gafoor MH, et al. Conservative management of thoracobiliary fistula. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73(4):1088–1091.

- Davies HE, Davies RJ, Davies CW. Management of pleural infection in adults: British Thoracic Society pleural disease guideline 2010. Thorax. 2010;65(Suppl 2):ii41–ii53.