Volume : 1 | Issue : 1

Research

Determining Safe Maximum Temperature Point (SMTP) for Polyacrylamide Polymer (PAM) in saline solutions

Kingsley Godwin Uranta, Sina Rezaei Gomari, Paul Russell, Faik Hamad

School of Science and Engineering, Teesside University, Middlesbrough TS13BA, United Kingdom

Received: December 04, 2017 | Published: January 24, 2018

Abstract

Polyacrylamide (PAM) and partially hydrolysed polyacrylamide (HPAM) are the most used water soluble polymers in Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) applications because they represent a powerful means of increasing the viscosity of injection water and most importantly, improving mobility ratio. However, they exhibit limited stability in harsh reservoir conditions of elevated temperature and high salinity, which is a serious technical challenge. This paper describes a correlation analysis of the gradient of PAM hydrolysis and viscosity as a function of time, temperature (within the range of 25 to 93°C) and salinity, to determine the safe maximum temperature point (SMTP) during improved and enhanced oil recovery (IOR/EOR) applications. The results indicate that different saline solutions such as NaCl, CaCl2 and NaHCO3 contains different SMTPs. At 5% NaCl, the SMTP was about 71°C, while for a combined saline solution containing 9% NaCl and 1% CaCl2 the SMTP was 78°C while it was 65°C for 3% NaCl and 1% NaHCO3. However, the results indicate that a saline solution containing chemical properties of alkaline/acid behaviour, such as NaHCO3, hydrolysed more rapidly due to its lower SMTP value. Accordingly, this report provides insights into the chemistry behind PAM degradation and can help in predicting the maximum safe temperature point of polyacrylamide operations in the presence of brine at any ageing time of interest during chemical IOR/EOR techniques.

Keywords: polyacrylamide, polymer stability, salinity, divalent cations, safe maximum temperature point (SMTP)

Introduction

Oil is found in underground porous sandstone or carbonate rock and its recovery takes place in three phases. The first phase is primary oil recovery, where the energy within the reservoir is utilised to displace the oil from the reservoir to the wellbore and up to the surface production facilities.1 The second phase is secondary oil recovery is when water or gas is injected into the reservoir to maintain its pressure and to displace the oil to the wellbore, up to the surface facilities. Once secondary oil recovery is exhausted, it is likely that 60–80% of the oil remains in the reservoir because only 20–40% of potential oil extracted during the primary and secondary oil recovery phases.2 The application of the EOR, or tertiary phase, is the next option, providing the opportunity to extract up to 30% of the original oil in place (OOIP) and to help meet growing global demand for continuous supply of oil in future.

The EOR process includes thermal recovery, gas injection and chemical injection. Chemical injection or chemical flooding is a major component of EOR and classified as polymer, surfactant or alkaline flooding. Each chemical EOR method has advantages but polymers are the most commonly utilised, most mature, most environmental friendly and least expensive.2-4 Polymer EOR materials are polyacrylamides (PAMs) or Xanthan gum, and polyacrylamide and partially hydrolysed polyacrylamide (HPAM) are the most used water soluble polymers in EOR applications because they represent a powerful means of increasing the viscosity of injection water and, most importantly, improving mobility ratio and reducing water production and hence sweep efficiency is increased. However, these materials exhibit limited stability in harsh reservoir conditions of elevated temperature and salinity, and this poses a particularly demanding technical challenge.5-20

Polymer selection depends on the temperature and salinity of the reservoir and care must be taking to ensure that the polymer does not degrade as it moves through the reservoir. One possible solution is to prevent or mitigate against ionic interaction with thermally hydrolysed PAM as to maintain a safe maximum temperature.17,21

Studies have claimed that gels produced with polyacrylamide used for the treatment of reservoirs with temperatures below 75°C.7,22 However, in hotter reservoirs the acrylamide groups of the polymers become hydrolysed to carboxylate groups, which can cause excess cross-links with divalent cations such as Ca2+ and Mg2+, which are often present in the environment.18,20,23-24 At elevated temperature an increase in carboxylation could occur, resulting in significant changes in the properties of the PAM solution, such as rheological behaviour, reduced viscosity and altered phase behaviour.

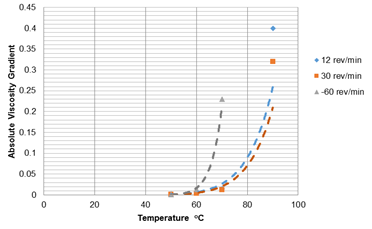

Elevated temperature is defined in this paper as a temperature above the safe maximum reservoir temperature, at which a particular polymer gel solution becomes unstable. Safe maximum temperatures for various water soluble polymers are categorised as low, high or ultra-high,23 as indicated in Figure 1 which represents in plot (a) the low and moderate safe temperature range up to 100°C, in plot (b) the high safe temperature range between 100–150°C, and in plot (c) ultra-high safe temperatures of above 150°C.

|

Figure 1 Various water-soluble polymer gels with maximum safe temperatures.11-13,15,19-21,23,28-32,41 |

Several ideas has been develop by researchers to avoid or minimize the degradation caused by dissolved oxygen, elevated temperatures and high salinity. These includes: (a) addition of oxygen scavengers such as methanol (CH3OH) or thiourea to minimize oxygen degradation,4,25-26 (b) The operation of HPAM at elevated temperatures in the absence of oxygen and divalent cations,27 (c) a pre-flush with fresh water to reduce high salinity4 and (d) a hardness limit in brines for various temperatures, for example at 2,000 mg/l for 75°C, 500 mg/l for 88°C, 270 mg/l for 96°C, and less than 20 mg/l for temperatures up 204°C.19 Moreover, in line with the aforementioned ideas, other types of polymer or combined polymers have been developed. Examples are the acrylamide copolymer N-polyvinyl pyrrolidone (N-VP), 2-acrylamide-2-methyl-propane sulfonate (AMPS),28 polyacrylamides of hexamethylenetetramine (HMTA), hydroquinone (HQ) or terephtalaldehyde, terphtalic acid with hydroquinone, and polyacrylamide and t-butyl acrylate ester (PAtBA) cross-linked with polyethyleneimine (PEI).20,29-32

Polyacrylamide and t-butyl acrylate ester (PAtBA) cross-linked with polyethyleneimine (PEI) as an organic cross-link has proved stable at a maximum safe temperature range of about 80°C to 177°C.31,33 According to Vasquez,34 when PAtBA is cross-linked with derivatized (d-PEI), it replaces the normal PEI resulting in an excellent gelation time of about 192–206°C. This implies that PAtBA cross-linked with derivatized (d)–PEI has the broadest temperature range for applicability and provides excellent permeability reduction with a good deep penetration of gel into the pore matrix. Xanthan gum is a biopolymer that has similar problems to those of polyacrylamide (PAM). However, it can operate effectively within a range of 75-80°C.35 At this temperature range, they hydrolyse in the presence of divalent cations such as Ca2+ and Mg2+ and the hydrolysed polymers precipitate, leading to a change in the gel's molecular structure or solution viscosity and this affects its stability over time.18-19,30

Moreover, because polymer (polyacrylamide) selection is based on the temperature and salinity of the reservoir, it is of primary importance in terms of effectiveness in application and operation to ensure that when a PAM solution is injected into the reservoir it will remain effective and stable under reservoir conditions (temperature and salinity) over a long period of time. This means that polyacrylamide stability in different temperature and salinity conditions becomes important, because these conditions can lead to the degradation of PAM solutions when injected into a reservoir. Therefore, it becomes paramount to develop a clear understanding of the chemistry behind the mechanisms that affect PAM performance and to find a correlation to determine SMTP in saline solution.

Mechanisms of PAM degradation

Harsh reservoir conditions (high temperature and salinity) result in PAM instability.16,17,20 However, to stabilise PAM in oilfield applications, an understanding is required of the chemistry behind the factors that affect its performance, such as alkalinity, elevated temperature, high salinity and presence of divalent cations and dissolved oxygen.17,36-37 Consequently, these conditions cause PAM to be open to anionic functionality that interacts with monovalent or multivalent cations, which in turn results in the loss in molecular weight of PAM or reduced solution viscosity.

Effect of hydrolysis and elevated temperature

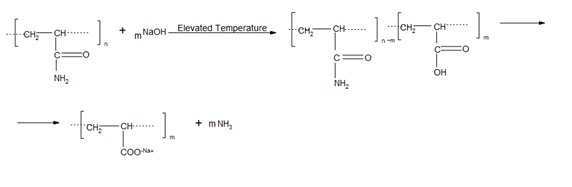

Polyacrylamide (PAM) is a synthetic water-soluble polymer and is electrically neutral in its pure state.37 PAM hydrolyses when mixed with an alkaline solution such as sodium hydroxide (NaOH) or when subjected to elevated temperatures, and its amide groups are converted into carboxylate groups,15,37 as shown in Figure 2. A carboxylate group carries a negative charge and represents a reactive site, promoting ionic interaction or cross-linking with molecules such as monovalent and divalent cations.

The polyacrylamide structure is composed of a carbon–carbon backbone hung with amide groups. It reacts with water to form carboxylic acid with a structural formula of R-COOH at elevated temperatures, while the amide group hydrolyses to form carboxylate groups. An elevated temperature acts as an initiator by providing the activation energy to promote the hydrolysis of the amide groups into carboxylate groups. The mechanism of chemical transformation is in Figure 3.

In a further step, the carboxylic group converted into a carboxylate group (RCOO-) through the loss of a proton (H+), as shown in equation 1.

(1) |

The carboxylate group is now free to undergo interaction with monovalent (NaCl) and multivalent ions, especially CaCl2 and MgCl2, as shown in Figure 3.

Effect of water salinity (divalent cations)

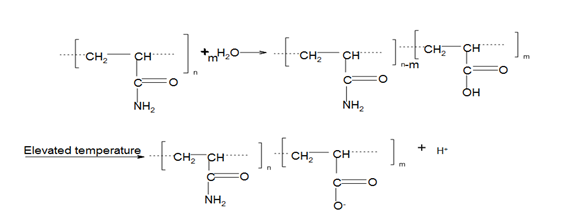

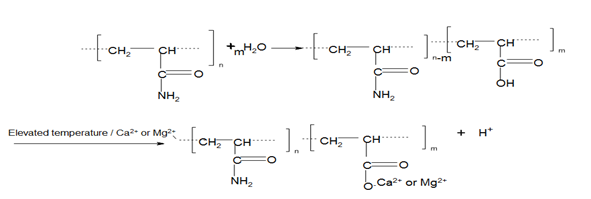

Water salinity is a measure of the total dissolved ions, such as Na+, K+, Ca2+ and Mg2+, carried by water that naturally exist within the pores of a reservoir sedimentary rock. When water containing monovalent (NaCl) and multivalent ions (predominantly CaCl2 and MgCl2) interact with PAM at elevated temperature in the reservoir, the amide group (CONH2) hydrolyses and results in the formation of carboxylate (RCOO-) ions. The subsequent interaction of carboxylate ions with the divalent Ca2+ and Mg2+ cations, leads to a sharp reduction in viscosity of polyacrylamide (PAM) solution. However, the exact chemistry is in Figure 4. Nevertheless, the degree of hydrolysis at which PAM will separate from the solution depends directly on the concentration of divalent cations and is inversely proportional to temperature.

Effect of elevated temperature and divalent cation level on polymer gel

Elevated temperatures and the presence of divalent cations (Ca2+ and Mg2+) effects during applications of water-soluble polymer (PAM) for improved secondary recovery or enhanced oil recovery may results in polymer syneresis and precipitation.

Polymer Syneresis

Polymer syneresis is a phenomenon where the polymer gel structure collapses, expelling water and in turn resulting in the contraction or shrinkage of the volume of the gel.17,21,38 According to Albonico and Lockhart,17 it is reasonable to expect that severe syneresis could result in a reduction of 90% or more of the original gel volume, and this could have a significant impact on the performance of a gel within porous reservoir rock. However, the percentage of syneresis could be determined in laboratory by calculating the difference between the weights of a sealed vial containing polymer gel before placed in the oven and the weight of a vial in which syneresis has occurred, the differences are divided by the initial weight of the sealed vial containing polymer gel multiplied by one-hundred.

There are two ways in which syneresis may occur: (1) excessive cross-linking [20,31]; and (2) at elevated temperatures or in conditions of high salinity.39 Excessive cross-linking, occurs during the transformation of polymer solution into gel via a chemical cross-linker. In this process, the cross-linker freely bonds the reactive groups to the polymer chains, and the effective molecular weight of the polymer increases. Consequently, if too much cross-linker is present in the vicinity, cross-linking may continue beyond the point of gelation, the polymer starts to contract in volume, and water is expelled.20

Karimi et al.,40 demonstrated how excess cross-linker could lead to syneresis in an experiment using four different weight ratios of polymer to cross-linker with a polymer concentration of 11,000 ppm and at a temperature of 80°C. The polymer-to-cross-linker weight ratios were 10 to 20; no syneresis occurred after 150 days but with a ratio of 40 to 60, syneresis occurred and increased. It became obvious that once the cross-linker concentration exceeds a certain value, the rate of syneresis starts to increase.

Meanwhile at an elevated temperature and in conditions of high salinity, syneresis could occur when the polyacrylamide solution with high salinity is place in an oven over an extended period. The polyacrylamide solution experiences hydrolysis and the acrylamide groups on the polymer backbone converted into acrylate, further interaction with divalent cations leads to the syneresis of the polymer gel. According to Karimi et al.'s40 experimental report, syneresis occurred when polyacrylamide (PAM) was placed in an oven for 6 months at temperatures of 80 and 100°C, but did not occurred when it was placed in the oven at 30 or 60°C. The temperature increase from 30 and 60°C to 80 and 100°C respectively resulted in syneresis, with some degree of reduction in gel volume. This implies that, as the temperature increases, the percentage of syneresis increases. Karimi et al.40 also showed that salinity has an effect on syneresis by adding NaCl, MgCl2 and NaHCO3, however, reductions in the volume of the polymer gel was observe.

Polymer Precipitation

Polymer precipitation is the result of interaction between divalent cations and the carboxylate groups within the hydrolysed polymer.41 This interaction implies that, as the percentage of carboxylate groups increases, solubility decreases. However, if this happens to excess, it will eventually amount to precipitation and the polymer solution will not transform into polymer gel.18,21,31,41 For instance, Muller et al.,16 stated that the viscosity of highly hydrolysed PAM sharply decreases when small quantities of CaCl2 added. The decrease is sharper with divalent cations than with monovalent salts but precipitation could occur in combined salts.

Chemical degradation

Chemical degradation of polymer gel is caused by many factors such as; high reservoir temperatures and oxygen contamination by free radical generation.4,25,36 According to Shupe,35 chemical degradation of PAM maybe caused by oxygen, which in turn could create a reaction with metals or metal ions. In the oxidization process, oxygen is a major means to accelerate the metal–induced degradation and more importance is the reaction that occurs between oxygen and ferrous ions to form radicals as shown in equation 2 and 3, which subsequently reacts with the polymer molecule to initiate a degradation chain reaction.38

(2) |

|

(3) |

For instance, the oxidization of Fe2+ to Fe3+ produces a free radical O-. Then the highly reactive oxygen-anion radical O- may become attached to the polymer chain to produce peroxide and break the backbone. Oxidization could also proceed via the free radical mechanism.25 According to Fenton,42 this mechanism occurs via a solution of hydrogen peroxide and an iron catalyst, and is used to oxidize contaminants or wastewater. The chemical reaction creates two different oxygen-radical species, H+ + OH-, with water as the by-product in the case of PAM. The active intermediate HO* in equations 4 to 7 can react with ferrous iron, hydrogen peroxide or other components contained in the reaction mixture. As shown in equation 2, iron (II) oxidized by hydrogen peroxide to become iron (III), forming a hydroxyl radical and a hydroxide ion in the process. The iron (III) is then reduced back to iron (II) by another molecule of hydrogen peroxide forming a hydroperoxyl radical and a proton, the step by step reaction are shown in equations 5 to 8 and it proposed by Haber and Weiss.43

(4) |

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

|

(7) |

>Results and discussion

Based on the above discussion and previously published data on the properties of PAM, the following sections attempt to deduce correlations between temperature and saline concentration and the degree of hydrolysis and thus the viscosity of PAM solutions.

Correlation of temperature on the degree of hydrolysis (DH) of PAM

According to Borling et al.,37 the proportion of amides group that maybe converted to carboxylate could called degree of hydrolysis (DH). When the value of DH varies from 0 to 60%, the polymer in this form is referred to as a partially hydrolysed polyacrylamide (HPAM). Ward14 explained that the loss the viscosity of solution in formation water or brine is the major problem encountered in the use of HPAM for improved oil recovery, due to the presence of monovalent ions and multivalent cations at elevated temperatures.

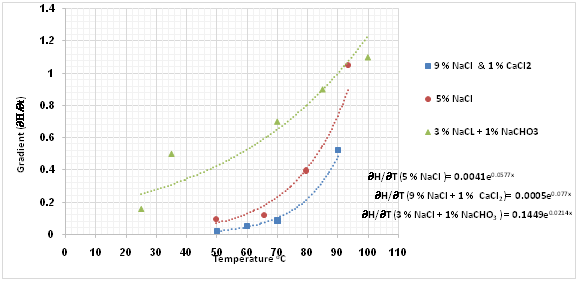

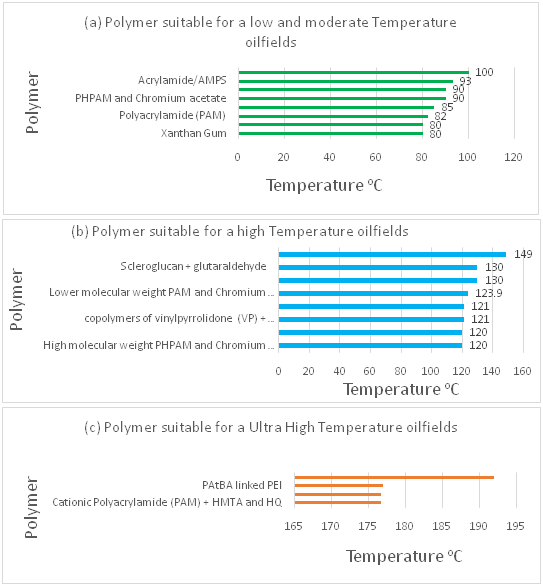

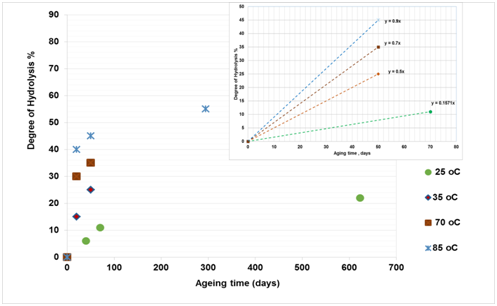

The effect of elevated temperatures on the degree of hydrolysis (DH) of PAM was analysed in three different oilfield brines: (5% NaCl), (9% NaCl and 1% CaCl2), (3% NaCl and 1% NaHCO3)12-13,37 to ascertain suitable safe maximum temperature (SMTP) of PAM in EOR application. Figure 5 shows the relationship between degree of hydrolysis (percentage) and ageing time (days) for PAM solutions at temperatures ranging from 25 to 93°C in the presence of 5% NaCl (Figure 5a), 9% NaCl and 1% CaCl2 (Figure 5b) and 3% NaCl and 1% NaHCO3 (Figure 5c). The plots show two regimes, the first of which represents the linear and the second the non-linear curve. The degree of hydrolysis seems to be sensitive to temperature change, where an increase in temperature results in a higher degree of hydrolysis. Moreover, an increase in degree hydrolysis observed when there was salts additive into the polymer solution. For all cases in the first regime, degree of hydrolysis (∂H) appears to exhibit a linear relationship with time as shown in equation 8:

(8) |

Where is the gradient of degree of hydrolysis against time.

|

Figure 5(a) Effect of temperature on hydrolysis of PAM in the presence of 5% NaCl.18 The curve for each temperature can be divided into two regions, the first representing the linear and second the non-linear curve. The plot at the top of the figure is related to the first region from which the gradient was determined. |

|

Figure 5(b) Effect of temperature on hydrolysis of PAM in the presence of 9% NaCl -1% CaCl2.19 The curve for each temperature could be divided into linear and non-linear regions. The plot at the top of the figure is related to the first region from which the gradient was determined. |

|

Figure 5(c) Effect of temperature on hydrolysis of PAM in the presence of 3% NaCl -1% NaHCO3.24 The curve for each temperature can be divided into linear and non-linear regions and the plot at the top refers to the linear region from which the gradient was determined. |

However, for all cases in the second regime, degree of hydrolysis (∂H) shows an increase in form of exponential decay with time as in equation 9.

(9)

Where is the intercept at the degree of hydrolysis, k is the gradient or slope.

Comparing results from three different studies,18-19,24 it can be concluded that, as the temperature increases, the gradient DH of PAM for both regimes increases and hence the stability of the polymer is reduced. Furthermore, the higher the temperature, the more rapidly the DH of PAM increases in the presence of divalent ions (CaCl2) and monovalent salts (NaCl) and the ageing times also reduced. For instance, as shown in Figure 5b for the second regime, it is clear that the percentage DH of PAM increased by 12-38% after 578 days ageing time at temperatures of 50, 60 and 70°C, while at 90°C the percentage DH increased to 58% with a lower ageing time of 154 days. This implies that, at higher temperature such as 90°C, the more hydrolyzed the PAM becomes and the ageing time is reduced. This is also applicable to the first regime with a linear relationship, where at higher temperature the ageing time is less, and at lower temperature, the ageing time is longer.

To gain a better understanding of the SMTP for the hydrolysis of PAM in the presence of saline solution, the next step involves plotting the gradient change in hydrolysis against temperature. The results as presented in Figure 6, showing a sudden shift from a slow to a high rate of hydrolysis at a certain temperature. This temperature could be defined as the safe maximum temperature point (SMTP), which varies as the ambient solution changes. In the presence of 9% NaCl and 1% CaCl2, this (SMTP) shift was observe at 74°C, while for 5% NaCl and 3% NaCl and 1% NaHCO3 solutions it is observed at about 71°C and 65°C respectively. Based on this, it is clear that the hydrolysis of PAM varies with salinity and hence so does its stability. The abnormally low temperature of 65°C observed for 3% NaCl and 1% NaHCO3 combined salts could be because of increased alkalinity of this solution, which suppresses the SMTP.

Correlation of temperature with the viscosity of PAM

The viscosity of a polymer solution varies widely with temperature. It is obvious that a change in the viscosity of a polymer solution with temperature is associated with concurrent change in the volume of the polymer. This is because, as temperature increases, the hydrolysed polymer solution and become open to anionic charge attached to the polymer backbone. According to Bill Meyer Jr.,44 the temperature dependence of viscosity maybe found to follow the simple exponential relationship in the Arrhenius equation, as stated in equation 10.

(10) |

Where ![]() is viscosity in mPa.s, E is the activation energy for viscous flow, A is a constant, R is gas constant, and T is temperature.

is viscosity in mPa.s, E is the activation energy for viscous flow, A is a constant, R is gas constant, and T is temperature.

From the Arrhenius equation, the viscosity of the polymer solution (![]() ) depends directly on the ratio of the activated energy (E) of the viscous flow of the polymer solution to temperature. This implies that the viscosity of PAM, its longevity (ageing time) and the thermal stability of the polymer solution depend on reservoir temperature.

) depends directly on the ratio of the activated energy (E) of the viscous flow of the polymer solution to temperature. This implies that the viscosity of PAM, its longevity (ageing time) and the thermal stability of the polymer solution depend on reservoir temperature.

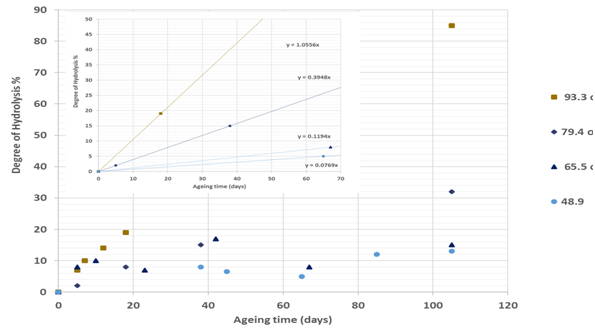

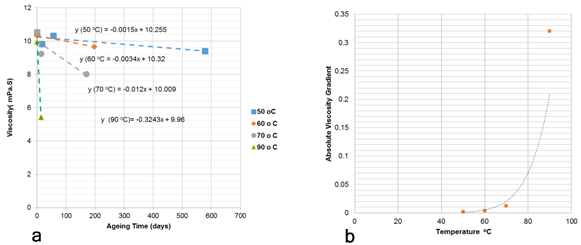

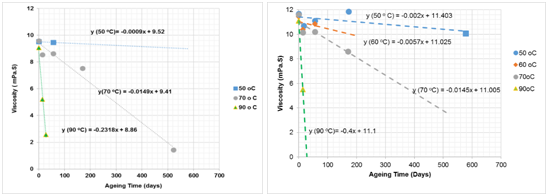

The effect of temperature on the viscosity of PAM against ageing times as seem in Figure 7a for the solution of 9% NaCl and 1% CaCl2 at 30 rev/min. At 50°C, the reduction in viscosity seem to be linear against time at a lower rate, while at the higher temperatures of 70 and 90°C a drastic shift in behaviour is seen where viscosity decreases at a much higher rate.

This shift in the polymer’s viscosity is seen in Figure 7b by plotting the absolute values of viscosity gradients extracted from Figure 7a. Figure 7b, which was used to obtain the safe maximum temperature point (SMTP) for the application of a polymer in a saline solution, in a similar approach to that obtained from the gradient of the degree of hydrolysis. It is worth mentioning that the SMTP obtained from viscosity data is similar to that obtained from hydrolysis data for the same saline solution, which shows the accuracy of the proposed method in determining the polymer SMTP for a specific saline solution.

|

Figure 7 (a) Effect of temperature on viscosity of PAM against ageing time and |

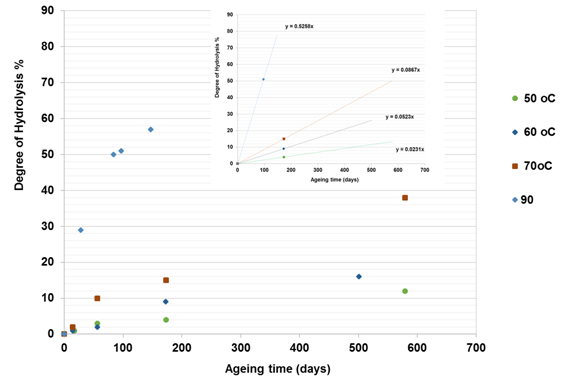

As reported by Stahl and Schulz,45 the polymer solutions used in an oilfield are non-Newtonian fluids. As shear rate is a function of viscosity, any changes in mechanical degradation, which may occur in pipes, through chokes, valves or pumps above certain velocity or pressure levels, can influence the solution’s properties. Accordingly, at a low shear rate, the polymer fluid behaves as a Newtonian fluid and thus the viscosity does not vary with shear rate. However, as the shear rate increases the polymer molecules deform and their viscosity decreases. Such a situation, where the viscosity of the polymer solution decreases with increasing shear rate is termed shear thinning. The effect of shear thinning on SMTP as investigated through fitting data measured for a saline solution of 9% NaCl and 1% CaCl2 at 60 and 12 revolutions per minute (rpm) (which are two and five times lower that the speed for the data presented in Figure 7). This data is shown in Figure 8. As temperature increases, viscosity decreases, and hence ageing time decreases. It is also worth mentioning that, following a decrease in the rotational speed (rev/min) of the device, a decrease in shear rate impacts on the viscosity results, especially at lower temperatures, where higher rotational speed increases, the viscosity in contrast to the lower rotational speed shows the normal and expected trend.

|

Figure 8 Effect of temperature on viscosity of PAM against ageing times for 9% NaCl + 1% CaCl2 for: |

The absolute values of viscosity gradient for the data presented in Figures 7a and 8, and as plotted in Figure 9, act as a function of temperature. The estimated SMTP values for these solutions at 30, 12 and 60 rev/min are 74, 78 and 63°C respectively in the presence of 9% NaCl and 1% CaCl2. Comparing these results, it is apparent that the SMTP of 60°C for the higher shear rate decreased to about 25°C, which indicates that the polymer becomes unstable with a shorter ageing time at higher shear rates.

Conclusions

Based on the results obtained from the SMTP correlation analysis, the following conclusions were drawn:

- ifferent saline solutions like NaCl, CaCl2 and NaHCO3 have different SMTPs.

- At 5% NaCl, the SMTP was about 71°C, whereas for a combined saline solution containing 9% NaCl and 1% CaCl2, the SMTP was 78°C while it was 65°C for 3% NaCl and 1% NaHCO3.

- A saline solution that has the chemical properties of alkaline/acid behavior, like (NaHCO3), hydrolyzed faster due to its lower SMTP value.

- SMTP obtained from viscosity data is similar to that of hydrolysis data for same saline solution.

- Understanding the precise chemistry behind the mechanism of PAM degradation and mitigation could facilitate higher SMTPs during PAM applications.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to express their appreciation to the Petroleum Technology Development Fund (PTDF) in Nigeria and Teesside University for their support.

Nomenclature

A |

Arrhenius equation constant |

CaCl2 |

Calcium Chloride |

DH |

Degree of hydrolysis |

Hydrolysis gradient |

|

E |

Activation energy for viscous flow |

EOR/IOR |

Enhanced oil recovery/Improved oil recovery |

MgCl2 |

Magnesium chloride |

NaCl |

Sodium chloride |

NaHCO3 |

Sodium bicarbonate |

NaOH |

Sodium hydroxide |

PAM |

Polyacrylamide |

R-COOH |

Carboxylic acid |

SMTP |

Safe maximum temperature point |

T |

Temperature |

µ |

Viscosity |

References

- Sun Y, Saleh L, Bai B. Measurement and impact factors of polymer rheology in porous media. INTECH Open Science / Open Mind. 2012:187−188.

- Abidin AS, Puspasari T, Nugroho WA. Polymer for enhanced oil recovery technology. Procedia Chem. 2012;(4):11−16.

- Chiappa L, Lockhart TP, Mennella A, et al. Water production control with relative permeability modifiers. In: 16th World Petroleum Congress. World Petroleum Congress. 2000.

- Shupe RD. Chemical Stability of Polyacrylamide Polymers. SPE 9299 paper presented at the 55th Annual Technical. Conference and Exhibition held in Dallas. 1981:1513−1529.

- Lopes LF, Silveira BMO, Moreno RBZL. Rheological evaluation of HPAM fluids for EOR applications. International Journal of Engineering & Technology. 2014;14(3):35−41.

- Katarzyna L. Comparative studies of rheological properties of polyacrylamide and partially hydrolyzed polyacrylamide solutions. J Appl Polym Sci. 2007;103:2235−2241.

- Li X, Xu Z, Yin H, et al. Comparative studies on enhanced oil recovery: thermoviscosifying polymer versus polyacrylamide. Energy Fuels. 2017;31(3):2479−2487.

- Zhu D, Wei L, Wang B, et al. Aqueous hybrids of silica nanoparticles and hydrophobically associating hydrolyzed polyacrylamide used for EOR in high-temperature and high-salinity reservoirs. Energies. 2014;7:3858−3871.

- El Karsanin KS, Al-Muntasheri GA, Sultan AS, et al. Impact of salts on polyacrylamide hydrolysis and gelation: new insights. J Appl Polym Sci. 2014;41185:1−11.

- Zhu Y, Lei M, Zhu Z. Development and performance of salt-resistant polymers for chemical flooding. SPE 172784, Paper presented at Middle East Oil & Gas Show and Conference, held in Manama, Bahrain. 2015:1−13.

- Mungan N. Shear viscosities of ionic polyacrylamide solutions. Society of Petroleum Engineers Journal. 1972;12(6):469−473.

- Knight BL. Reservoir stability of polymer solutions. Journal of Petroleum Technology. 1973;25(5):618−626.

- Gogarty WB. Mobility control with polymer solutions. Society of Petroleum Engineers Journal. 1967;7(2):161−173.

- Ward JS, Martin FD. Prediction of viscosity for partially hydrolyzed polyacrylamide solutions in the presence of calcium and magnesium ions. Society of Petroleum Engineers Journal. 1981;21(5):623−631.

- Cheremisinoff NP. Handbook of Engineering Polymeric Materials. 1st edition. New York: Marcel Dekker. 1997;61−65

- Muller G, Fenyo JC, Selegny E. High molecular weight hydrolyzed polyacrylamides. III. Effect of temperature on chemical stability. J Appl Polym Sci. 1980;25:657−633.

- Albonico P, Lockhart TP. Divalent ion-resistant polymer gels for high-temperature applications: syneresis inhibiting additives. In: SPE International Symposium on Oilfield Chemistry. Society of Petroleum Engineers. 1993.

- Moradi–Araghi A, Doe PH. Hydrolysis and precipitation of polyacrylamides in hard brines at elevated temperatures. SPE Reservoir Engineering. 1987;189−198.

- Ryles RG. Chemical stability limits of water-soluble polymers used in oil recovery processes. SPE Reservoir Engineering. 1988:3(1):23−34.

- Mohammad S, Mohsen V, Ahmad KD, et al. Polyacrylamide gel polymer as water shut–off system: preparation and investigation of physical and chemical properties in one of the Iran oil reservoirs condition. Iranian Journal of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering. 2007;26(4):99−108.

- Albonico P, Lockhart T. Stabilization of polymer gels against divalent ion–induced syneresis. J Pet Sci Eng. 1997:61−71.

- Levitt DB, Slaughter W, Pope GA, et al. The effect of redox potential and metal solubility on oxidative polymer degradation. SPE Reservoir Evaluation & Engineering. 2011;14(3):287−298.

- Dovan HT, Hutchins RD, Sandiford BB. Delaying gelation of aqueous polymers at elevated temperatures using novel organic crosslinkers. In: International Symposium on Oilfield Chemistry. Society of Petroleum Engineers. 1997.

- Levitt DB, Pope GA, Jouenne S. Chemical degradation of polyacrylamide polymers under alkaline conditions. SPE Reservoir Evaluation & Engineering. 2011;14(3):281−286.

- Sheng J, Leonhardt B, Azri N. Status of polymer flooding technology. Journal of Canadian Petroleum Technology. 2015;54(2):116−126.

- Seright RS, Campbell A, Mozley P, et al. Stability of partially hydrolyzed polyacrylamides at elevated temperatures in the absence of divalent cations. SPE Journal. 2010;15(2):341−348.

- Bedaiwi E, Al-Anazi BD, Al-Anazi AF, et al. Polymer injection for water production control through permeability alteration in fractured reservoir. NAFTA. 2009;60(4):221−231.

- Fernandez IJ. Evaluation of cationic water-soluble polymers with improved thermal stability. In: SPE International Symposium on Oilfield Chemistry. Society of Petroleum Engineers. 2005.

- Abedi LM, Vafatia SM, Baghban SM, et al. Gelation time of hexamethylenetetramine polymer gels used in water shutoff treatment. Journal of Petroleum Science and Technology. 2012;2(2):3−11.

- Guang Z, Cailidai Q, Mingwei Z, et al. Study on formation of gels formed by polymer and zirconium. J Solgel Sci Technol. 2013;65(3):392−398.

- Kelland MA. Production Chemicals for the Oil and Gas Industry. 2nd edition, CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group London. 2009;23−36.

- Doe PH, Moradi-Araghi A, Shaw JE, et al. Development and evaluation of EOR polymers suitable for hostile environments. J Polym Sci A1. 1987;17(3):659−672.

- Al-Muntasheri GA, Nasr-El-Din HA, Al-Noaimi K, et al. A study of polyacrylamide-based gels crosslinked with polyethyleneimine. SPE Journal. 2009;14(2):245―251.

- Vasquez J, Dalrymple ED, Eoff L, et al. Development and evaluation of high-temperature conformance polymer systems. In: SPE International Symposium on Oilfield Chemistry. Society of Petroleum Engineers. 2005.

- Seright RS, Henrici BJ. Xanthan stability at elevated temperature. SPE Reservoir Engineering. 1990:52−60.

- Schurz GF, Mckennon KR. Aqueous solutions of polyacrylamide stabilized with thiourea. 1966.

- Borling D, Chan K, Hughes T, et al. Pushing out the oil with conformance control. Oilfield Review. 1994:44−58.

- Crees OL, Whayman E, Willersdorf AL. The degradation of high molecular weight flocculants. Paper made available from Sugar Research Institute, Mackay, Queensland, Australia. 1973:263−266.

- Bryant SL, Rabaioli MR, Lockhart TP. Influence of syneresis on permeability reduction by polymer gels. SPE Production & Facilities. 1996;11(04):209−215.

- Karimi S, Kazemi S, Kazemi N. Syneresis measurement of the HPAM-Cr (III) gel polymer at different condition: an experimental investigation. J Nat Gas Sci Eng. 2016;34:1027−1033.

- Zaitoun A, Potie B. Limiting conditions for the use of hydrolyzed polyacrylamides in brines containing divalent ions. In: SPE Oilfield and Geothermal Chemistry Symposium. Society of Petroleum Engineers. 1983.

- Fenton HJH. LXXIII.—Oxidation of tartaric acid in presence of iron. Journal of the Chemical Society, Transactions. 1894;65:899−910.

- Haber F, Weiss J. Hydroperoxide. Naturwissenschaften. 1932;20(51):948−950.

- Meyer B. Polymer Science Textbook. 1st edition, New York: John Wiley & Sons, USA. 1971:185−191.

- Stahl GA, Schulz DN. Water Soluble Polymers for Petroleum Recovery. 1st edition, Great Britain Springer Science and Business Media. 1987;15:103−145.